(G S Manku, email: manku.gs@gmail.com)

(4.3).1 ATOMIC VOLUME

(4.3).1.1 Definition

Atomic volume (AV), also called the gram atomic volume, for an element, is defined as the volume occupied by 1 mole or Avogadro number of atoms of the element. If ρ is the density of an element having atomic mass A, then

AV = A/ρ = A × Vsp

where Vsp is the specific volume of element, defined as the volume occupied by 1 kg of element in liters.

Atomic volume of Avogadro number of atoms (not molecules) of an element depends upon a number of factors, which reduce the usefulness of the concept. For example,

- Elements have different atomicity, e.g., He, Ne, Ar, H2, O2 ,N2, P4, As4, S8, etc. The volume of one mole of Xn molecules cannot be considered to be equal to n times the volume of a mole of X atoms either at molecular level or in solid state.

- Atomic volume strongly depends on the structure adopted by the element in solid state. The fcc or ccp structures are close-packed structures and have less vacant space, while others like bcc are more open structures with more vacant space in its lattice.

- Many elements like carbon, sulphur, phosphorus, tin or arsenic exist in allotropic forms. Different allotropes have different densities due to the different arrangement of atoms.

- Density of a substance depends on the temperature and decreases with increase in temperature.

(4.3).1.2 Variation of Atomic Volume with Atomic Number

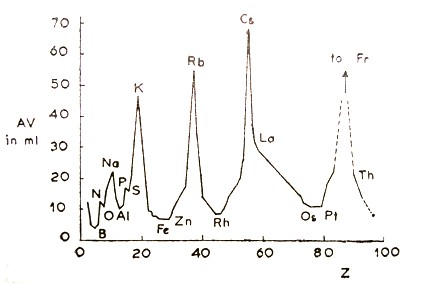

In spite of the limitations, atomic volumes of elements show some characteristic periodic trends. When AV is plotted against atomic number Z, following trends are observed [Figure (4.3).1].

Figure (4.3).1 Variation of Atomic Volume against atomic number Z

- Alkali metals: Due to the formation of a new quantum shell of electrons, the alkali metals have a much larger radius than the preceding halogens. Also, they form a more open body-centered (bcc) lattice. Therefore, they have a large atomic volume and are at local maxima in the curve.

- Variation along a Period for Representative Elements: As electrons are added in the valence shell, there is a decrease in atomic sizes and increase in the metallic character of elements with increasing nuclear charge after group 1. As a result, the density of the elements increases and their atomic volume decreases. However, with further increase in the valence shell electrons, the metallic character decreases and the elements become nonmetallic. Their density decreases and consequently, their atomic volumes increase.

- Transition Elements: When electrons are added in the d orbitals, the density of the element increases due to the decrease in their atomic radii. At the d10 configuration, the size increases abruptly due to the completion of subshell and the density decreases. Therefore, the transition elements lie at the minima of the atomic volume curve in the respective periods,

- Inner Transition Elements: The density of these elements increases much more in the f series because of

- Lanthanide Contraction: Due to the filling up of 14 electrons in the inner shell (n – 2)f orbitals, atomic size decreases for 14 elements.

- Proximity of the f orbitals to nucleus, which increases the effective nuclear charge on the valence shell electrons because of poor shielding due to penetration by outer electrons, and

- Greater increase in the nuclear charge in the series.

Hence, the stable, naturally occurring element with highest density is expected to be in the 5d series following the 4f elements. It should be the one which is just before the d10 configuration. This element is iridium (d96s0), which has density of 22.6 × 103 kg m–3.

(4.3).2 Covalent Radii of Atoms

It is difficult to define the radius of an atom or an ion. According to quantum mechanics, there is always some probability of locating an electron at any distance from the nucleus. Therefore, the radius of an atom or its ion will be infinite.

For practical purpose, the radius of species is defined as the distance up to which the nucleus exerts an effective control over its outermost electrons.

Radius of an atom is not a fixed quantity. It depends on the environments in which the atom is present, e.g., its oxidation state, the bond order, coordination number, metallic, covalent or ionic character of bonded formed, crystal and molecular structure, etc. Therefore, atoms are assigned a number of radii values, e.g., atomic radius, covalent radius, metallic radius, orbital radius, ionic radius, Bragg–Slater radius, van der Waal’s radius, etc. Each value is useful for a particular environment only and every set of values gives similar results in the observed trends in properties.

(4.3).2.1 Covalent Radius

Covalent radius (r) of an element X is equal to one half the inter-nuclear distance between the two X atoms bonded through a covalent bond. Depending upon the nature of bond formed, we have single bond radius, double bond radius and triple bond radius for same atom. For example, single bond radius of carbon atom = 77 pm because the C–C bond length in diamond (which contains single bond between two carbon atoms) is 154 pm. For radius of a double bonded carbon atom, we select the C=C bond length in ethene (CH2=CH2), while radius for a triple bonded carbon atom is taken from the bond length in ethyne (CH≡CH). (The radius of double bonded carbon = 66 pm, that for triple bonded carbon = 55 pm.)

The bond length (rA – B) between two atoms A and B is given as

rA – B = rA + rB – 9 |ΧA – ΧB |

where rA and r B are the atomic radii of A and B respectively, and ΧA and ΧB are their respective electronegativities. From the experimentally determined bond lengths Cl–Cl = 200 pm, C–Cl = 176 pm, C–Br = 194 pm, C–I = 214 pm, Si–I = 244 pm and Si–Cl = 202 pm, the average values of covalent radii for some single-bonded atoms can be calculated as Si = 157 pm, S = 104 pm, F = 72 pm, Cl = 100 pm, Br = 114 pm and I = 135 pm.

This relation does not hold if the A–B bond has some π character. As the π bonds have a shorter bond length than the σ bonds, the extent of π bonding decreases the observed bond length as seen for the observed and calculated bond lengths of Si–F = 156 (182), Si–Cl = 202 (217) or S–F = 156 (176) bonds (all values in pm).

(4.3).2.2 Metallic Radius

Metallic radius is defined as the one half of the distance between the nuclei of two neighboring atoms in a metallic lattice. This radius is smaller than the atomic radius of the isolated atom, but is larger than the single bond covalent radius. Typical values of metallic and covalent radii are K = 231 and 203 pm, Ba = 217 and 198 pm, Cr = 159 and 145 pm, respectively.

(4.3).2.3 Orbital Radius

Orbital radius is defined as the distance from the nucleus where the probability of finding the electron in an orbital is a maximum. Orbital radius is always less than the atomic radius, and is reduced by a factor of 1.5–2. Typical values are Na = 171 pm or Mg = 128 pm for 3s orbitals, and Al = 104 pm for 3s and 131 pm for 3p orbitals. Orbital radius can be defined for ions also, for example, for 2p orbitals, it is 25 pm for Na+ and 22 pm for Mg2+ ions.

For mono atomic anions, the orbital radii are almost the same as those for the atom.

(4.3).2.4 Van der Waal’s Radius

van der Waal’s radius for an atomic, ionic or molecular species is defined as one half of the shortest distance between the centre of two species in solid state. For example, the internuclear distances in solid helium, neon and argon are 280 pm, 308 pm and 384 pm respectively so that the van der Waal’s radii for these atoms are taken as He = 140 pm, Ne = 154 pm and Ar = 192 pm.

van der Waals radii are always larger than the atomic or molecular radii, and are sensitive to external conditions, including pressure and electrostatic fields in crystals. Typical values for van der Waal radii for atoms are H = 120 to145 pm, C = 165 to 170 pm, N = 155 pm, O = 150 pm, F = 150 to 160 pm, Na = 230 pm, Mg = 170 pm, and Ni = 160 pm.

(4.3).3 IONIC RADII

(4.3).3.1 Existence of Ions – The ED Map Radii

From wave mechanics, the radius of an isolated ion is infinite; there is definite probability of finding electron around the nucleus at any distance. The electrons are transparent to X rays, so that the position of electron cannot be located around the nucleus in an ionic compound or ionic lattice. Therefore, certain assumptions must be made to have a useful definition of ionic radius. These include (1) existence of ions, (2) correct apportioning of the interionic distance between the cation and the anion, and (3) additivity of ionic radii, i.r. constancy of ionic radii.

Ions are responsible for the luminescence of the Sun as well as existence of the Earth’s ionosphere. To have a useful concept of ionic radii, it is assumed that (1) ions are actually present in compounds, (2) ionic radii for cation and anion are additive and give the inter-ionic distances in crystals, and (3) inter-ionic distance in crystals can be correctly apportioned between the cation and the anion. However, an ion does not have a precisely defined radius; radius of the same ion changes from compound to compound.

Though ions do exist in solutions and in molten states, and the calculations based on the assumption that ions are present in ionic solids do provide accurate description of ionic compounds, a direct evidence of existence of ions is shown by the electron density maps (ED maps) for a few ionic solids using sophisticated X ray crystallography which gives both the internuclear distances as well as the electron density. The electron density changes continuously from nucleus of cation to nucleus of anions, but drops down to very low value of 0,2 electron per Ǻ3 (200 electron nm–3) in between. For NaCl, the evidence shows about 10.05 electrons around sodium ion and 17.85 electrons around chloride nucleus. 0.10 electrons simply vanish in the arbitrary integration in the internuclear space.

The difference between the ED map radius and Pauling’s ionic radius is taken to be due to the covalence in the compounds. This increases in the order K+ < Na+ < Li+ < Cu+; and Cl– < Br–.

A correct apportioning of internuclear distances is possible as these ionic radii are observed to be additive. The ionic radii are calculated from the internuclear distances in ionic crystals by assuming the radius of one ion. Though the ionic radii do not remain constant in different crystals, the variations are small, and the radii (in pm) are found to be as:

r(Na) = r(Li) + 25 ± 3 r(Cl) = r(F) + 50 ± 4

r(K) = r(Na) + 32 ± 2 r(Br) = r(Cl) + 16 ± 2

r(Rb) = r(K) + 14 ± 1 r(I) = r(Br) + 25 ± 1

(4.3).3.2 Molar Refractivity and Ionic Radii

The Lorenz – Lorentz equation can be used to experimentally determine the molar refractivity R, and calculate the ionic radii:

R = [ (n2 – 1 )/(n2 + 2)] [M / ρ)

where, n is the refractive index of the material having molecular weight M and density ρ. The molar refraction is found to be additive and the refraction equivalent of atoms and bonds can be assigned. As R has the dimension of M/ρ, i.e., volume, the molar refraction for each ion can be put equal to r3 (r = radius of ion); r = kR1/3 (where k is a constant of proportionality). Thus for two ions:

(r1/r2) = (R1/R2)1/3

For NaF, internuclear distance = 233 pm, ionic refraction of sodium ion = 0.5 and of fluoride ion = 2.5, so that,

Radius of sodium ion = (0.5)1/3 / [(0.5)1/3 + (2.5)1/3] = 85.25 pm.

(4.3).3.1 Landè’s Radii

Landè’ (1920) assumed that in ionic compounds, Li+ is the smallest ion. In its halides, therefore the smaller-sized cation will be surrounded by and touching the larger-sized halide ions, whereas the halide ions will be touching one another. From the experimental value of I–I distance in LiI = 426 pm, the shortest I–I distance in iodides, ionic radius of iodide ion was taken as 213 pm. The internuclear distances in other halides were then used to calculate Landè’s ionic radii as Li+ = 74 pm, Na+ = 99 pm, K+ = 140 pm, F– = 132 pm, Cl– = 172 pm, Br– = 188 pm.

(4.3).3.2 Pauling’s Univalent Radius

Assuming that ionic radius of an ion is proportional to its effective nuclear charge (Z*), Pauling used the inter-ionic distances in crystals of isoelectronic pairs of Na+ F–, K+ Cl–, Rb+Br– and Cs+I–. Each of these pairs has same radius ratio of ions and same extent of ionic and covalent character. Pauling calculated the ionic radii of these ions by (1) calculating Z* using Slater’s rules, (2) using internuclear distance in crystals, and (3) assuming that for isoelectronic ions, radius is inversely proportional to Z*, i.e.,

r = c/Z*

where c is a constant of proportionality depending on the number of electrons in the ions. The following Example shows the procedure used by Pauling.

Numerical Example

The shortest distance between nuclei of sodium and fluorine atoms in crystal of sodium fluoride is 231 pm. Determine the Pauling’s radii for Na+ and F– ions.

Solution: If rNa+ and rF– are the radii of the respective ions, then

rNa++ rF– = 231

Both rNa+ as well as rF– ions are isoelectronic ions and have same electronic configuration 1s22s22p6. Screening constant (σ) for the outer shell electrons is

σ = 7 × 0.35 + 2 × 0.85 = 4.15.

Therefore,

ZNa+* = ZNa – σ = 11.00 – 4.15 = 6.85,

ZF–* = ZF – σ = 9.00 – 4.15 = 4.85.

Now writing rNa+ = c/ ZNa+* and rF– $r(\ce{F-}) = c/ ZF-* and using the values of effective nuclear charges as calculated above,

c /6.85 + c /4.85 = 231

On solving, we get c = 656 (for neon configuration), from which

rNa+ = 656/6.8 = 95.8 pm

rF– = 656/4.8 = 135.2 pm

(4.3).3.3 Pauling’s Crystal Radii

If the value of c = 656 pm is used for calculating the ionic radius of Mg2+ or O2– ions, we obtain values which are very large (experimental values are Mg2+ = 67 pm, O2– = 140 pm):

r Mg2+ = 656 / (12 – 4.85) = 83.6 pm

r O2– = 656 / (8 – 4.85) = 170.4 pm

These values are, however, known as the univalent radii (r11), and are referred to as the radii of the ions in a lattice field of 1:1 ions. When corrected for the compressions of ions in a field of multivalently charged ionic particles, the Born’s expression for the lattice energy in crystals can be used to calculate the crystal radius (rc) for ions with charges i and j as

rc = rij × c– 1/(n – 1)

where n, the Born’s coefficient = 7 for neon, 9 for argon, 10 for krypton and 12 for xenon shells. Using this relation, we obtain radius of Mg2+ ion = 62 pm and O2– ion = 140 pm in MgO crystals, which is close to the experimental values.

(4.3).3.4 Pauling’s Crystal Radius

Pauling’s radii, (r11) calculated as above, agree well with the radii of the mono-valent ions. For bivalent ions and other multivalent ions, the radii obtained are much higher than the actual values. For example, for magnesium oxide, the sum of ionic radii of the ions comes out to be 257 pm whereas the observed internuclear distance is 205 pm. This is because the r11 values are calculated for the 1:1 lattice, and are not corrected for addition compression of ions in a 2:2 lattice. They can be correlated to each other as shown below.

The equilibrium distance req in ionic crystals consisting of ions carrying charges of z+ and z– is given as

req = (4πε0nB/A z+z–e2)1/(n – 1)

where n is the Born coefficient, A is the Madelung constant for the ionic lattice, and B is the inter-electronic repulsion term according to Bohr. Substituting z+ = 1 and z– = 1 for the r11, and z+ = zi and z– = zj for the rij, we get

r11 = (4πε0nB/Ae2)1/(n – 1)

and, ris = (4πε0nB/ijAe2)1/(n – 1)

so that division gives

rij = r11 (ij)1/(1 – n)

When I = j = 2, we obtain

rc = rij (2)2/(1 – n)

The value of Born exponent n is 2 for He, 7 for Ne, 8 for Ar, 9 for Kr, 10 for Xe and 12 for Rn configurations..

Using n = 7 for magnesium and oxide ions ( Ne configuration), we get the crystal radii values which are close to the observed ionic radii of these ions:

Ionic radius, rc for magnesium ions = 81.3 (2)2/(1 – 7) = 62 pm

Ionic radius, rc for oxide ions = 175.4 (2)2/(1 – 7) = 140 pm

(4.3).3.5 Ionic Radii and Coordination Numbers

The effective ionic radius increases with the coordination number of the ion in the lattice. For example, effective ionic radius for calcium ions (for different coordination numbers) is 102 pm (6), 107 pm (7), 112 pm (8), 118 pm (9). 128 pm (10) and 135 pm (12); for oxide ions is 135 pm (2), 136 pm (3), 138 pm (4), 140 pm (6) and 142 pm (8) respectively. Variations in the size of the cations are more than that for the anions.

(4.3).3.6 Non-Spherical Ions – Yatsmirskii’s ionic radii

Most of the anions, e.g., nitrate, carbonate, sulphate, cyanide or acetate are not spherical. For these ions, effective ionic radii are calculated from the lattice energy of the compounds and are called thermochemical radii or Yatsmirski’s thermochemical radii. Some typical values are carbonate = 185 pm, nitrate = 190 pm, cyanide = 182 pm, hydrogencarbonate = 163 pm, sulphate = 230 pm, phosphate = 238 pm, and acetate = 160 pm. These values have no physical significance but are useful in calculating the stabilities of the ionic compounds.

From group theory, the presence of spherical ions is justified for ions in high-symmetry crystal lattice sites only, like Na and Cl in halite or Zn and S in sphalerite . A distinction can be made the by using point symmetry group of the lattice site which are cubic groups Oh and Td in NaCl and ZnS respectively. For ions in lower symmetry structures, the ions ma not remain spherical as shown by electron density measurements, especially in lattice sites of polar ions, which belong to vC1, vC1h, Cnv or Cnv, n = 2, 3, 4 or 6 symmetry. For example, in pyrites. monovalent chalcogens have ellipsoidal symmetry.

(4.3).3.7 Bragg–Slater Radius

To calculate the inter-ionic distances in ionic as well as covalent crystals within an error of ± 6 pm, an empirical rule, known as Bragg–Slater rule, is very useful. According to this rule, given by Slater, the ionic radii of cations are 85 pm less and those of anions are 85 pm more than the atomic radius of the atoms. The radii are supposed to increase in units of 5 pm. Some values of Bragg–Slater radii are Na+} = 95 pm, Ca2+ = 110 pm, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2=+, Zn2+ 135 pm, Mg2+ = 150 pm, F– = 130 pm, O2– = 140 pm, Cl– = 185 pm, Br– = 195 pm, I– = 215 pm.

(4.3).3.8 Shannon and Prewitt Ionic Radius

Earlier values of the ionic and related radii were based on the Pauling’s ionic radii for ions. However, to accommodate more compounds and incorporate the covalence in bonding, these values were revised by Shannon and Prewitt. They compiled a data for the atomic and ionic radii for the elements by studying crystallographic data for a large number of ionic compounds. To be consistent with Pauling, Shannon used ionic radius of oxide ion = 140 pm. These are called ‘effective’ ionic radii. These are additive and are inter-consistent with one another. These values are about 14 pm larger for the cations and 14 pm smaller for the anions. However, Shannon also included data based on ionic radius of oxide in as 126 pm as he felt that these values, called “crystal” ionic radii are more closely related to the physical size of ions in solids. Further, he also gave data for radii in coordination compounds for ions with different coordination numbers. The two sets of data are listed in the two tables below.

(4.3).3.9 Soft-sphere model

For many compounds, the model of ions as hard spheres does not correspond to the distance between the ions in crystals. In the soft-sphere model, the overlap between the “electron clouds” of ions is allowed and the relation between the soft-sphere radii of ions, rs+, rs– and the internuclear distance rc is given as

rck = rs+k + ts–k

where k is a constant between 1 and 2, depending on the crystal structure and the number of electrons in ions. For group 1 halides with NaCl structure k = 1.667 works the best. The values of internuclear distances are LiCl calculated as 257.2 (observed value = 257.0), LiBr = 274.4 (275.1), NaCl = 281.9 (282.0) and NaBr = 298.2 (298.7) (in pm).

(4.3).4 VARIATIONS IN RADII OF ELEMENT

(4.3).4.1 Variations in a Group

Representative Elements: The size of an atom or ion depends on the principal quantum number of the outermost shell. For representative elements, we have the following trends.

- The atomic and ionic sizes increase with increase in atomic number down the group because of the addition of new shells of electrons. The increase is more for the lighter members than for the heavier members as shown by the ionic radii:r

Table (4.3).1 Shannon and Prewitt’s Ionic radii of ions having noble gas shells

Group Charge Shannon and Prewitt’s Ionic Radii (in pm)

————————————————————————————-

1 + 1 Li = 90, Na = 116, K = 152, Rb = 161, Cs = 186

2 + 2 Be = 59, Mg = 86, Ca = 114. Sr = 132, Ba = 149

13 + 3 Al = 68, Ga = 76, In = 94, Tl = 103

14 + 4 Si = 54, Ge = 67, Sn = 84, Pb = 92

15 N = 150*, P = 190, As = 200

16 – 2 O = 126, S = 170, Se = 185, Te = 207

17 – 1 F = 119, Cl = 167, Br = 187, I = 206

—————————————————————————————

* : Pauling’s values for the ions

2. For the heavier members, effect of increase in the new quantum shell of electrons is much less than the effect of increase in nuclear charge. This may be due to the poor shielding of valence shell electrons by the inner d and f orbital electrons.

3. Transition Elements: Between the 3d and 4d series, 18 electrons are added. Of these, ten electrons are poorly shielding d electrons. Therefore, effect of added shell is not fully reflected in the sizes of these atoms and ions. Further, additional lanthanide contraction between 4d and 5d series, leads to a drastic decrease in sizes of the 5d In many cases, sizes of the 5d elements are lower than those of the 4d elements: ionic radius of Zr4+ = 80 pm, Hf4+ = 78 pm.

(4.3).4.2 Variations in a Period

When electrons are added in a valence shell, the nuclear charge also increases. This results in increase in nucleus–electron electrostatic attraction between the valence shell electrons, which increases directly with nuclear charge.

Increase in the interelectronic repulsions amongst the electrons in the valence shell} due to

(1) Increase in the number of electron pairs present in the shell; two electrons can form only one electron pair, three electrons form three pairs, while four electrons form six pairs of electrons (number of electron pairs for n electrons in a shell = nC2 ), and

(2) Increase in the repulsion faced by the incoming electron due to the increasing negative charge density in the shell. The interelectronic repulsions increase more drastically with increasing number of valence shell electrons. Initially, nucleus–electron attractions are stronger than the interelectronic repulsions and the atomic size decreases as the nuclear charge Z increases. However, with increasing nuclear charge, the electronic repulsions increase more rapidly than the increase in nucleus–electron attractions. As a result, initially the atomic size decreases with Z, but later in the series, size may actually increase with increase in Z. For p block elements, size increases after p configuration, and the p6 (group 0 or 18) elements have higher atomic and radii then the corresponding p (group 17) elements.

In a period, the following trends are observed.

- Isoelectronic ions: Isoelectronic ions have same number of electrons. The ionic radii of isoelectronic ions decrease with increasing Z or Z* as is seen in the following order

O 2– > F– > Na+ > Mg2+ > Al3+

K+ > Ca2+ > Sc3+ > Ti4+

Table (4.3).2 Ionic radii of Isoelectronic ions in pm and Ionic Charge

————————————————————————————–

Configuration +1 +2 +3 +4 +5

————————————————————————————–

Cations

1s2+ Li (90) Be (59) B (41)

1s22s22p Na (116) Mg (86) Al (68) Si (54) P (52)

2s23s23p6 K (152) Ca (114) Sc (89) Ti (68)

3s23p63d10 Cu (91) Zn (88) Ga (76) Ge (67)

4s24p6 Rb (166) Sr (132) Y (104) Zr (86) Nb (78)

4s24p64d10 Ag (129) Cd ( 99) In (94) Sn (83) Sb (74)

4s24p64d105s2 Sn(95) Sb (90)

4s24p64d105s25p6 Cs (181) Ba (149) La (117) Ce (101)

4f145s2 5p6 Yb (101) Lu (100) Hf (85) Ta (78)

5s25p65d10 Au (100) Hg (116) Tl (103) Pb (91.5)

5s2 5p6 5d106s2 Tl (164) Pb (133) Bi (117)

————————————————————————————–

Note: For noble gases, van der Waal radius are given, whereas for the ns2 ions, values are only approximate.

- Transition Elements: The incoming d electrons are added in the penultimate orbitals, and cannot shield the valence shell electrons completely (Slater’s rules). The effective nuclear charge increases and the atomic radius of the element decreases. This decrease in size continues up to the d10 configuration, when the radius increases abruptly due to the completion of d subshell [Table (4.3).3].

Further, as expected for transition metals also, the ionic radii of isovalent ions decrease with increasing Z.

Table (4.3).3 Atomic and Ionic radii of transition and inner-transition elements

in most common oxidation states (in pm)

——————————————————————————-

Element Atomic M+ M2+ M3+ M4+ M5+ M6+ M7+

———————————————————————————

Sc 162 88.5

Ti 147 100 81 74.5

V 134 93 88 72.5 68

Cr(ls) 128 85–94 75 69 63 58

Mn 127 97 78.5 73 66 56

Fe 126 90 78 58.5

Co 125 79 68.5 53

Ni(hs) 124 83 56 – 60[

Cu 128 91 81 68(Is)

Zn 134 88

Y 162 104

Zr 160 86

Nb 146 86 82 78

Mo 139 83 79 75 73

Tc 136 78.5 74 70

Ru 134 82 76 70.5 52(pl)

Rh 134 80.5 74 69

Pd 137 73 100 90 75.5

Ag 162 120 108 89

Cd 151 109

La 187 117.2

Hf 159 85

Ta 146 88 82 78

W 139 80 76 74

Re 137 77 72 69 67

Os 135 77 72.5 68.5 53

Ir 135.5 82 76.5 71

Pt 138.5 74 76.5 66.5 71

Au 162 151 99 72

Hg 151 133 116

La 188 117

Ce 180.8 115 101

Pr 182.4 113 99

Nd 181.4 129 112

Pm 183.4 111

Sm 122 95.8

Eu 208.4 117 94.7

Gd 180.4 107.8

Tb 177.3 106.3 90

Dy 178.1 121 105.2

Ho 104 104.1

Er 176.2 108

Tm 175.9 117 102

Yb 193.3 116 101

Lu 173.8 100

Ac 126

Th 179 105

Pa 163 116 104 92

U 156 116.5 103 90 87

Np 155 124 115 101 89 86 85

Pu 159 114 100 88 85

Am 173 140(8) 111.5 99

Cm 174 111 98

Bk 170 110 97

Cf 186 109 96

Es 186 93

—————————————————————————————-

Note: The ions are 6-coordinate, unless indicated by suffixes pl = panar, py = pyramidal, 4 = tetrahedral, 8 = coordination number 8.

- Inner Transition Elements: The atomic radius of these elements decreases much more in the inner transition or f series of elements because of the following.

- Lanthanide contraction: Due to the filling up of 14 electrons in the inner shell f orbitals, atomic size decreases considerably than that in case of the transition elements.

- Proximity of the f orbitals to nucleus, which increases the effective nuclear charge on the valence shell electrons because of poor shielding, and

- Greater increase in the nuclear charge in the series.